« Blood in the Mobile | Main | Cool tech toy: spherical drone »

Albert Borgmann to give Laing Lectures at Regent

By Rosie Perera | October 18, 2011 at 1:04 am

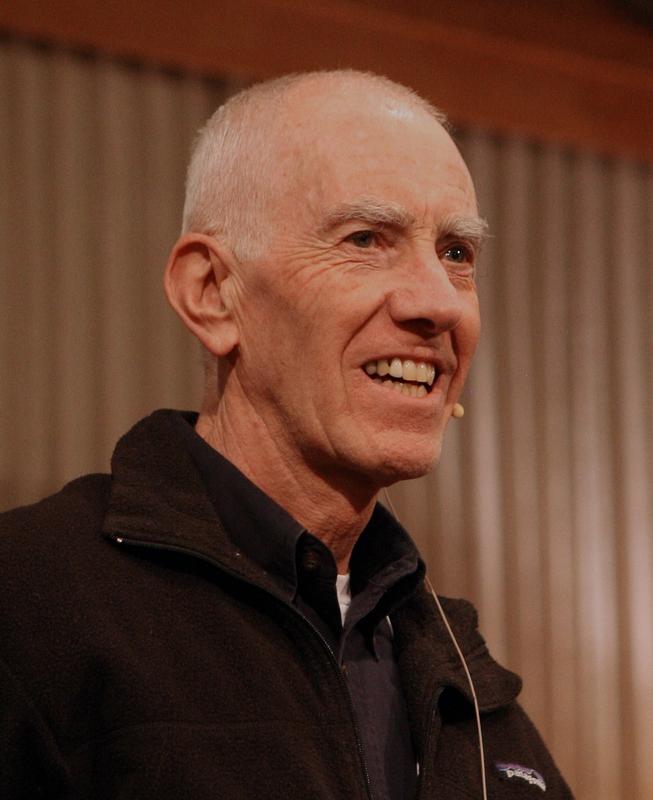

Albert Borgmann, a philosopher of technology from University of Montana, is coming to Vancouver to deliver the Laing Lectures at Regent College next week (Oct 19 & 20, “The Lure of Technology: Understanding and Reclaiming the World”), so I thought I’d devote a couple of posts to him and his work.

Albert Borgmann, a philosopher of technology from University of Montana, is coming to Vancouver to deliver the Laing Lectures at Regent College next week (Oct 19 & 20, “The Lure of Technology: Understanding and Reclaiming the World”), so I thought I’d devote a couple of posts to him and his work.

I met Dr. Borgmann at the Laity Lodge Consultation on Technology in March. Prior to that, I had studied his major work Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life (University of Chicago Press, 1984) for my master’s comps at Regent. I must say he is easier to understand in person than in writing, but maybe I found him so because I’d already absorbed his main ideas through much study. Anyway, he is a very congenial person and I am looking forward to seeing him again, though the more study and thinking I’ve done since embracing his ideas, the more unsure I am that I agree with him completely. He has become quite influential in the circles of philosophical and Christian thinking about technology, so I think it’s important to understand his contributions to the field, and perhaps push back a bit.

Borgmann is a Christian, though most of his writing does not assume that as his starting point. His only book aimed specifically at a Christian audience is Power Failure: Christianity in the Culture of Technology (Brazos, 2003), a collection of essays previously published, revised and arranged in some sort of cohesive order for this book. Though ostensibly written for the educated lay (as in non-philosophically trained) reader, it is, I confess, almost as hard to wade through as Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life (TCCL). Since he is pretty inaccessible to the general public, I present here my summary explanation of TCCL (edited down slightly from what I included in my comps paper). In a later post I will provide a critique.

Borgmann proposes that we think about technology in terms of what he calls the device paradigm. A device is something that procures for us a commodity (goods or services) without demanding any skill or attention of us. For example, a stereo provides the commodity of music without our having to know how it works, as opposed to playing a musical instrument which requires knowledge, practice and effort. The more sophisticated the device, the more incomprehensible and concealed from our view is its mechanism.

The more technology advances, the less aware we are of its background (the mechanics of how it works and the political and economic conditions under which it operates) when we consume its commodities. Commodities become disconnected from their contexts. Borgmann gives the example of TV dinners which are prepared instantly and eaten in a hurry without any depth; the fellowship of kitchen and table are missing, which subtracts from the meaning of the meal.

The promise of technology – that it would provide freedom from hardship, disease, and toil – has not materialized unambiguously. New freedoms are offset by increased burdens elsewhere. The benefits of technology are unjustly distributed. Perhaps the promise is too vague and not worth keeping. It results in the pursuit of “frivolous comfort.” (39) What was meant to give liberation and enrichment yields instead disengagement, distraction, and loneliness. (76)

Another problem is disorientation. In pretechnological society, one oriented oneself by reference to the sun. Today we have nothing around which to orient ourselves. We have lost what Borgmann calls focal things and practices. A focal practice is an activity which “can center and illuminate our lives…a regular and skillful engagement of body and mind.” (4) Playing a musical instrument is a prime example. A focal thing is something which is used in a focal practice, such as a violin. The promise of technology causes us to trade focal things for commodities and engagement in focal practices for diversion. We are left feeling a sense of loss and betrayal of the traditions to which we are indebted.

The device paradigm leaves a dichotomy between work and leisure and diminishes happiness in both. Technology has reduced work to degrading labor. While work bestows dignity, labor is drudgery. Increased technological affluence has brought with it a decline in reported happiness.

There was and remains an ideal of a life of leisure and the pursuit of excellence, which includes world citizenship, intelligence, physical valor, musical and artistic talent, and charity. This used to be the privilege of the elite, but advances in technology were supposed to make it available to the masses. But to whatever extent technology has provided us with more leisure time, we have not been using it to pursue excellence.

Since technology tends to be invisible under the device paradigm, and we live in an advanced industrial country, we are “implicated in technology … profoundly and extensively.” (105)

Borgmann wants to find a way for focal things to thrive in the midst of a technological context. Thus he proposes a reform of technology which “is neither the modification nor the rejection of the technological paradigm but the recognition and restraint of the pattern of technology so as to give focal concerns a central place in our lives.” (211) Technology itself is not a focal practice. Indeed, it has “a debilitating tendency to scatter our attention and to clutter our surroundings.” (208) “If we are to challenge the rule of technology, we can do so only through the practice of engagement.” (207) This suggests a return to focal things and practices in our lives today. Borgmann highlights “running and the culture of the table” as two such practices capable of providing a centering and orienting focus in the midst of a technological culture. A focal practice can also be a sacred one, a reenactment of some key event, such as the eucharistic meal.

UPDATE: Arthur Boers, whom I also met at the Laity Lodge Consultation on Technology, has just written a book which is a pastoral appreciation and application of Borgmann’s ideas. It’s called Living into Focus: Choosing What Matters in an Age of Distractions. It’s available now for pre-order through Brazos Press, Amazon, and other book sellers.

Topics: Uncategorized | No Comments »

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.